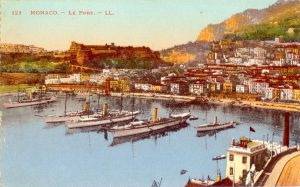

Yachts in the harbour at Monaco pictured around the early twentieth century. In the background the royal palace occupies a hilltop position.

The tiny principality of Monaco is the second-smallest sovereign state in the world, and could easily fit into London’s Hyde Park with room to spare. Yet it has become one of the world’s most prestigious and wealthiest resorts.

But in earlier times things were very different. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the rulers of Monaco imposed exorbitant taxes on the 1,000 farmers who made up most of the population, and a time came when the citizens could barely continue to support the extravagant lifestyle of the royals. Faced with a choice between an uprising on the part of his subjects or bankruptcy, the sovereign prince –Charles III – searched for a solution. It was, in fact, Princess Caroline, his mother, who had the brainwave that was to rescue the Prince from ruin, as well as putting Monaco on the map. Caroline had recently visited the spa town of Bad Homburg – a tiny, independent territory in what is now Germany. With the co-operation of the ruler, a successful casino had been established there by a Frenchman, François Blanc. In return for a licence to operate, Blanc paid a generous annual sum to the Prince, as well as meeting most of the expenses of the state, such as defence and law-enforcement.

The gambling business was highly profitable. Since all casino games are biased in favour of the house, most clients lost money in the long run. But there were some notable exceptions: in 1852, Prince Charles Lucien Bonaparte – a nephew of the former Emperor Napoleon – won a huge sum of money and had the good sense to depart with it before the casino had a chance to claw it back again. Whenever a gambler had won so much that the cash reserves at that particular table were used up, he was said to have broken the bank. François Blanc invented a ceremony in which the table was temporarily closed down and a black cloth laid upon it. Uniformed attendants brought out more cash from the vaults to pay the rest of the fortunate gambler’s winnings and to replenish the table’s cash reserve. After a decent interval the black cloth was removed, and the table re-opened so that play could recommence.

Blanc realised that news of large wins like this would spread quickly, and that the publicity would entice many other people to come and try their luck, thinking that they might replicate the winner’s success. The casino always got over its short-term loss quickly and profited from the extra business.

Based on these past accomplishments, Blanc was invited by the Prince to set up a similar operation in Monaco. But at first Blanc refused, and other entrepreneurs stepped in. With great difficulty they opened a casino at a site overlooking Monaco’s harbour but, during one six-day period, there was only one visitor, who won the princely sum of 2 francs. Two others then arrived and lost 205 francs. Bored croupiers took to standing around outside the casino watching for the approach of possible customers.

Fearing bankruptcy, Prince Charles of Monaco made a last desperate appeal to François Blanc, who now agreed to take over the casino, improve the facilities, and run the operation. In return for this privilege, he would pay the Prince 150,000 francs each year, plus ten per cent of the casino profits. And as he signed the contract, Blanc suggested that the site of the new casino should be named Monte Carlo (‘Mount Charles’) in the Prince’s honour. Under Blanc’s leadership the Casino took off and by 1869 it was contributing such large amounts to the economy of Monaco that the citizens were absolved of all taxes – a situation which still exists to this day. Soon both the casino and the principality of Monaco were booming. When Blanc died in 1877 he left a going concern and a fortune of 72 million francs. His son, Camille, eventually took over as chief director and for the time being the future looked rosy.

Everything changed when the Prince died in September 1899. He was succeeded as ruler of Monaco by his son, Albert, who – unlike his father – strongly objected to the casino, and despised the Blanc family and their mercenary ways. He had allegedly told a friend that he would close the casino down if he could. This became a distinct possibility when he married Alice Heine, an immensely rich American widow. With access to the prodigious wealth of her family he was no longer dependent on the Blanc family or what he saw as their tainted money.

By the summer of 1891 it seemed that the casino’s days were numbered, especially when newspapers reported that the Prince now planned to close it down and turn the building into a free hospital. Camille Blanc even contacted the Prince of Liechtenstein to explore the possibility of relocating the casino there – though the area was far less desirable than Monaco and more difficult for most regular customers to reach. Blanc also halted work on a costly new extension to the gambling salons.

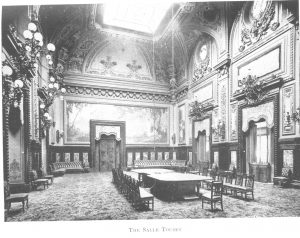

The Salle Touzet pictured in the early twentieth century. Work on this salon had begun in 1890 but was suspended until the future of the casino was assured

It was at this precise time that a rather ordinary-looking Englishman named Charles Deville Wells arrived in Monte Carlo and began to play roulette with an abandon that suggested ‘a mad millionaire trying to get rid of his capital’. Each day at noon he was waiting on the doorstep when the casino opened, and he gambled non-stop until it closed at 11.00 p.m. In the course of five days he broke the bank not once, but several times, winning £40,000 – equivalent to at least £4 million in present-day values. He returned a few months later, repeated the performance, and left with a further £20,000 (£2 million today). In Britain, Wells and his exploits were hot topics. Newspaper readers never seemed to tire of his adventures, and composer Fred Gilbert immortalised his exploits in the popular music-hall song, ‘The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.’

Wells’ ability to break the bank with apparent ease provoked much discussion and speculation – especially when it was revealed that he had previously claimed to have developed and patented many valuable inventions. He had induced investors to buy a share in his ideas, but no-one had ever received a penny in return. One of his backers, the sister of a distinguished judge, had lost the equivalent of almost £2 million, while another had blithely entrusted him with over £1 million in present-day terms.

In view of this, people began to wonder whether Wells had somehow defrauded the casino, as well. It certainly seemed a possibility.

Or had he developed an infallible system for winning at roulette? This was the explanation he gave at the time and on many occasions in subsequent years. Yet witnesses who had watched him at the casino said they discerned no obvious pattern in his play: instead they attributed his success to his willingness to take risks, and the ability to keep calm when under pressure.

Whatever his secret was, the casino was busier now than it had ever been. Visitors jostled for a place at the tables in the hope of replicating Wells’ astonishing success. Casino profits rocketed, and the price of the shares – most of which were owned by the Blanc family – soared to an all-time high. Wells himself seems to have foreseen this result, too, for it is known that before leaving Monaco he purchased shares to the value of £200,000 in today’s money.

In the event, the threatened closure of the casino never took place. Camille Blanc was finally able to renegotiate his contract with the new Prince of Monaco – but at a hefty price. The Prince would receive 1,000 casino shares and a cash payment of 125 million francs. Blanc was also bludgeoned into paying 7 million francs for improvements to local amenities.

A century and a quarter later, Monaco is as enchanting to tourists as it has always been. As a prominent tax haven it has grown into a magnet for the rich, and almost a third of its residents are millionaires. In recent years it has diversified into banking and tourism, though the casino is still its most famous attraction, and continues to underpin the local economy.

And once in a while casino staff and gamblers alike still speak in hushed tones about “the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo”.

The above is reproduced from the August 2016 edition of the History Press Newsletter. You can sign up to receive every edition of the newsletter here.